January 25, 2020

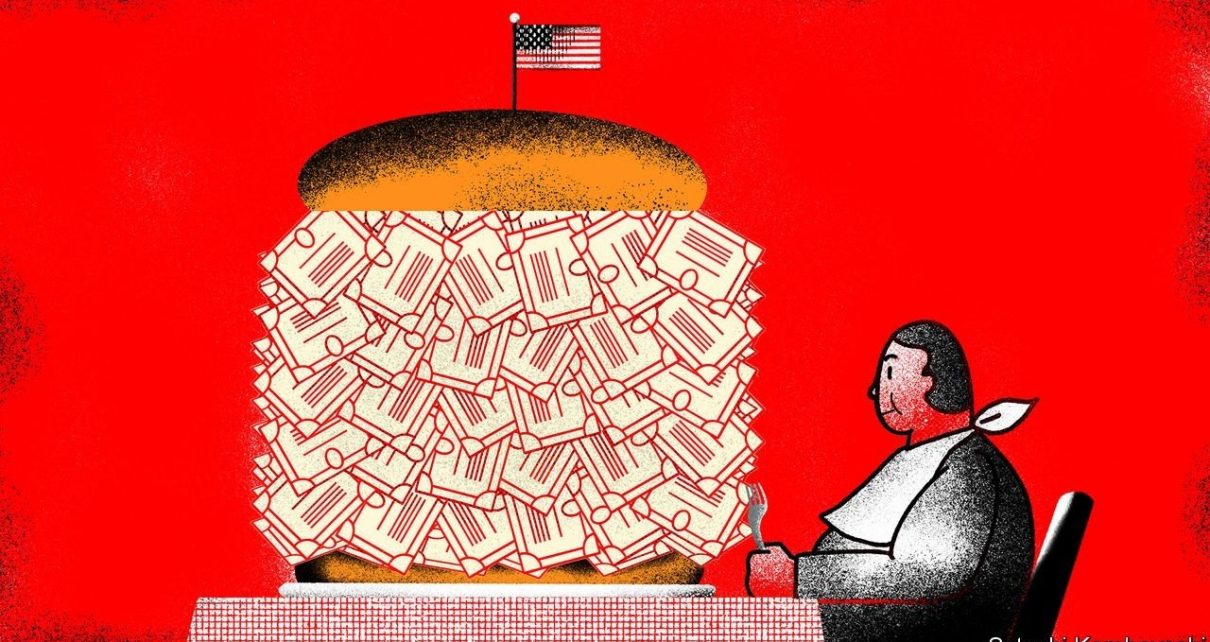

IN THE GOOD In the old days, the US budget deficit was yawning when the economy was weak and shrinking when it was strong. It went from 13% to 4% of GDP during Barack Obama’s presidency, as the economy recovered from the 2007-09 financial crisis. Today, unemployment is at its lowest for 50 years. Yet borrowing is increasing rapidly. The tax cuts in 2017 and the increase in public spending widened the deficit to 5.5% from GDP, according to IMF data — the biggest, by far, of any rich country.Listen to this story

Enjoy more audio and podcasts on ios or Android.

It could soon expand even more. President Donald Trump is believed to want a pre-election giveaway. Fox News is inundated with “Tax Cuts 2.0” rumors. This month, the Treasury announced it would issue a 20-year bond, which would lengthen the average maturity of its debt and lock in low interest rates for longer. All of this is quite a change for many Republicans, who once accused Mr. Obama of debauchery, but now say multibillion-dollar deficits are no big deal. Democratic presidential candidates, meanwhile, talk about Medicare for All and a Green New Deal. A new consensus on fiscal policy has descended on Washington. Can he hold on?

Tax hawks fear that continued high levels of government borrowing could lead to economic chaos as the engine overheats. Many of them felt justified by the turbulence of the last year in the repo market, through which financial companies lend each other. To buy treasury bills, investors must hand over money to the government. Thus, the increase in bond issuance has led to an increase in demand for cash reserves borrowed from the repo markets, causing rates to skyrocket. The Federal Reserve was forced to step in to provide short-term funding.

Aside from this setback, however, the markets caught the US debt frenzy in stride. In recent months, the yield on ten-year Treasuries has been below 2%. Interest repayments, as a percentage of GDP, are half of the level of the early 1990s. And this, despite a much higher outstanding debt compared to GDP, a sign of investors’ voracious appetite for safe assets.

One of the sources of this demand is domestic investors. Much has been said about the increase in corporate debt. Yet American companies are now net providers of savings to the rest of the economy, likely because the money they raised has been recycled back to investors in the form of dividends and share buybacks. These business savings have to be parked somewhere. Treasury bills are an obvious destination.

Post-crisis financial system reforms have also played a role. Commercial banks, for example, are now required to hold more high-quality liquid assets. Treasury bills are an ideal candidate, points out David Andolfatto of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. At the same time, a rule change at the end of 2016 reduced the attractiveness of money market funds that invest in corporate debt securities. This, in turn, has increased the demand for funds that invest only in treasury bills.

Households save more. When the financial crisis hit, families, fearing for their jobs and wages, began to put money aside. Despite the economic recovery, they have not stopped, perhaps due to the continuing economic uncertainty. The personal savings rate is much higher than it was in the 2000s. Over the past three years, household holdings of government debt securities have increased by 70%.

Domestic investors have absorbed two-thirds of the additional government borrowing since 2016. Foreigners have bought the remainder – the equivalent of $ 800 billion in treasury bills. As a result, America is now an even bigger net borrower from the rest of the world. Its current account deficit widened to around 2.5% of GDP.

It’s no surprise that investors have an appetite for US debt. Political uncertainty abounds, not least thanks to Mr. Trump’s enthusiasm for the threat of a trade war. There are few other paradises. Germany’s insistence on a very strict fiscal policy means there is an under-supply of bunds, argues Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank. Traders complain that the Japanese government bond market is illiquid.

The investors based in Europe seem to have been the most enthusiastic buyers (see chart). This partly reflects the large trade surpluses of several countries. Last year, Norway, a major oil exporter, doubled its holdings. But that doesn’t explain why Belgium, a country of 11 million people, is one of the biggest foreign buyers of treasury bills in the world. Although China’s official purchases appear stable, some suspect that some of its purchases are made through Belgian intermediaries.

Tax favors

Can the US public deficit remain so large for much longer? Some economists fear that lax fiscal policy in an era of low unemployment could cause the economy to overheat and increase inflation. This would force the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and government borrowing costs. So far, however, there are few signs of this. Inflation is strangely soggy; the Fed cut rates three times last year.

US fiscal lavishness could continue for now, especially if the Treasury borrows more on longer maturities. But whether it is economically reasonable, that is another matter. Despite all the looseness, in the long run GDP growth is medium and productivity growth low. Perhaps this is because the madness has been largely focused on tax giveaways, while federal capital spending has declined in proportion to government spending. US fiscal policy may not be dangerous, but it might not do much. ■

This article appeared in the Finance & economics section of the print edition under the title “The great Treasuries binge”